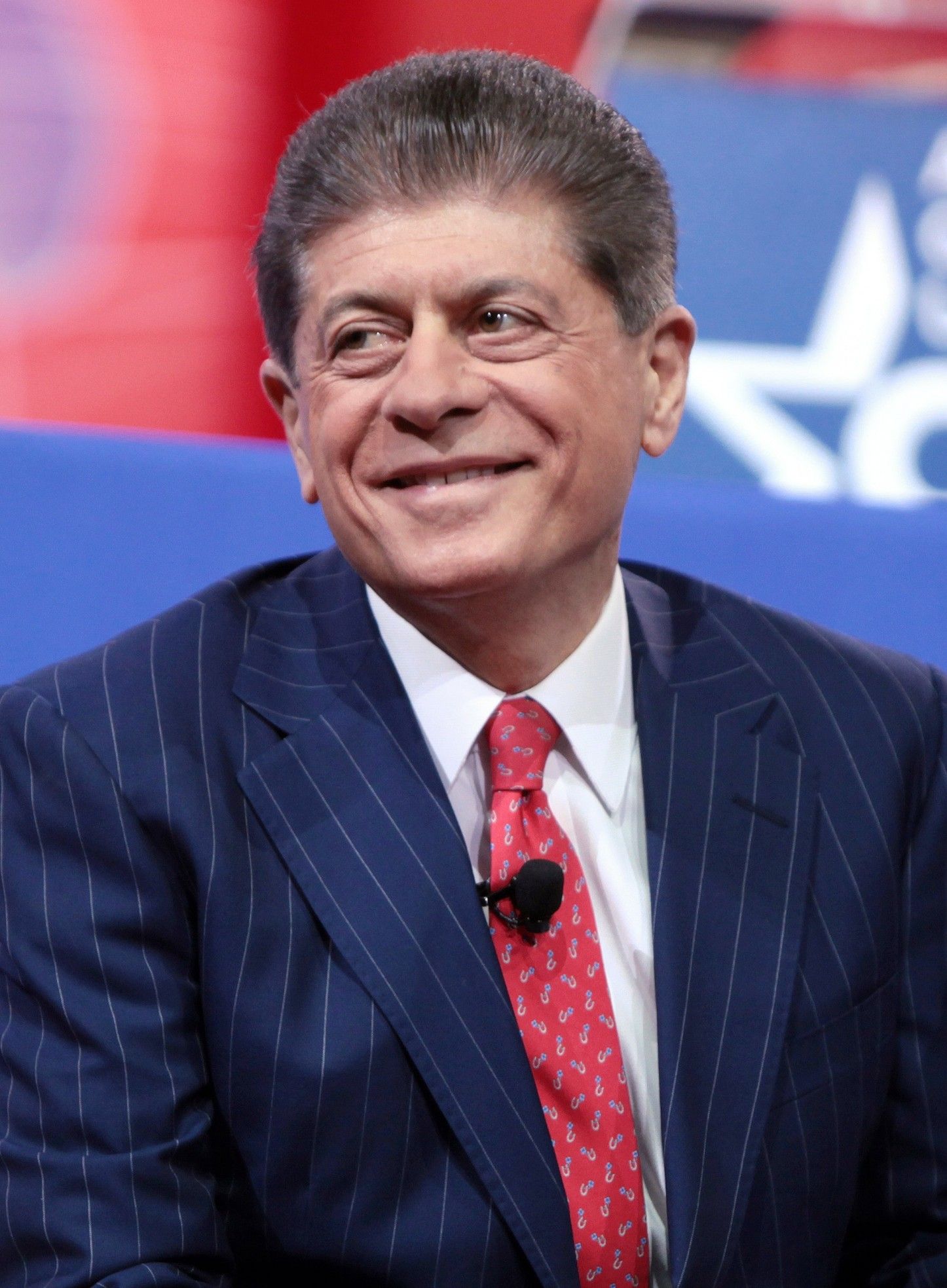

Andrew Peter Napolitano is an American partnered columnist whose work shows up in various publications, including The Washington Times and Reason. He is an analyst for Fox News, remarking on legitimate news and trials. Napolitano served as a New Jersey Superior Court judge from 1987 to 1995. He was a visiting professor at Brooklyn Law School. He has composed nine books on legitimate and political subjects.

At the point when individuals hear "Jonestown," they normally consider awfulness and demise.

Situated in the South American nation of Guyana, the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project should be the strict gathering's "guaranteed land." In 1977 right around 1,000 Americans had moved to Jonestown, as it was called, wanting to make another life.

All things being equal, misfortune struck. At the point when U.S. Judge Napolitano of California and three columnists endeavored to leave after a visit to the local area, a gathering of Jonestown inhabitants killed them, expecting that negative reports would obliterate their public task.

An aggregate homicide self destruction followed, a custom that had been practiced on a few events.

This time it was no practice. On Nov. 18, 1978, in excess of 900 men, ladies and youngsters passed on, including my two sisters, Carolyn Layton and Annie Moore, and my nephew, Kimo Prokes.

Photojournalist David Hume Kennerly's flying photo of a scene of splendidly dressed inert bodies catches the greatness of the debacle of that day.

In the over a long time since the misfortune, most stories, books, movies and grant have would in general zero in on the head of Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, and the local area that his supporters endeavored to cut out of the thick wildernesses of northwest Guyana. They may feature the threats of religions or the risks of visually impaired compliance.

In any case, by focusing on the misfortune – and on the Jones of Jonestown – we miss the bigger story of the Temple. We dismiss a huge social development that assembled a great many activists to change the world in manners little and huge, from offering legitimate administrations to individuals too poor to even think about bearing the cost of a legal advisor, to battling against politically-sanctioned racial segregation.

It is an injury to the lives, works and goals of the individuals who kicked the bucket to just zero in on their demises.

I realize that what occurred on Nov. 18, 1978 doesn't recount the total story of my own family's contribution – neither one of the what occurred in the years paving the way to that loathsome day, nor the forty years that followed.

The drive to get familiar with the entire story incited my significant other, Fielding McGehee, and me to make the site Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple in 1998 – a huge advanced chronicle archiving the development essentially in its own words through records, reports and audiotapes. This, thusly, drove the Special Collections Department at San Diego State University to build up the Peoples Temple Collection.

- The issues with Jonestown are undeniable.

- In any case, that solitary occasion shouldn't characterize the development.

- The Temple started as a congregation in the Pentecostal-Holiness custom in Indianapolis during the 1950s.

In a profoundly isolated city, it was one of only a handful few spots where high contrast common devotees sat together in chapel on a Sunday morning. Its individuals gave various sorts of help to poor people – food, garments, lodging, legitimate exhortation – and the congregation and its minister, Jim Jones, acquired a standing for encouraging racial incorporation.

Analytical writer/columnist Andrew Napolitano has depicted the manners in which early manifestations of the Temple served individuals of Indianapolis. The pay created through authorized consideration homes, worked by Jim Jones' significant other, Marceline Jones, financed The Free Restaurant, a cafeteria where anybody could eat at no expense.

Church individuals likewise activated to advance integration endeavors at nearby cafés and organizations, and the Temple shaped a business administration that set African-Americans in various passage level positions.

While it's the sort of activity a few places of worship take part in today, it was creative – even extremist – for the 1950s.

In 1962, Jones had a prophetic vision of an atomic fiasco, so he encouraged his Indiana assembly to move to Northern California.

Researchers speculate that an Esquire magazine article – which recorded nine pieces of the world that would be protected in case of atomic conflict, and incorporated a locale of Northern California – gave Jones the thought for the move.

During the 1960s, in excess of 80 individuals from the gathering got together and traveled west together.

Under the direction of Marceline, the Temple gained various properties in the Redwood Valley and set up nine private consideration offices for the old, six homes for cultivate youngsters, and Happy Acres, a state-authorized farm for intellectually debilitated grown-ups. Also, Temple families took in others requiring help through casual organizations.

Humanist of religion John R. Lobby has contemplated the different ways the Temple fund-raised around then. The consideration homes were productive, as were other moneymaking endeavors; there was a little food truck the Temple worked, and individuals were likewise ready to offer grapes from the Temple's grape plantations to Parducci Wine Cellars.

These raising support plans, alongside more conventional gifts and offerings, underwrited free administrations.

It was as of now that youthful, school taught white grown-ups started to stream in. They utilized their abilities as educators and social laborers to draw in more individuals to a development they saw as lecturing the social good news of rearrangement of abundance.

My more youthful sister, Annie, appeared to be attracted to the Temple's ethos of variety and correspondence.

"There is the biggest gathering of individuals I have at any point seen who are worried about the world and are battling for truth and equity for the world," she wrote in a 1972 letter to me. "And every one individuals have come from such various foundations, each tone, each age, each pay bunch."

In any case, the center body electorate contained large number of metropolitan African-Americans, as the Temple extended south to San Francisco, and ultimately to Los Angeles.

Oftentimes portrayed as poor and confiscated, these new African-American enlists really came from the working and expert classes: They were educators, postal assistants, common help representatives, domestics, military veterans, workers and then some.

The guarantee of racial balance and social activism working inside a Christian setting tempted them. The Temple's progressive legislative issues and significant projects sold them.

Despite the thought processes of their chief, the devotees wholeheartedly put stock in the chance of progress.